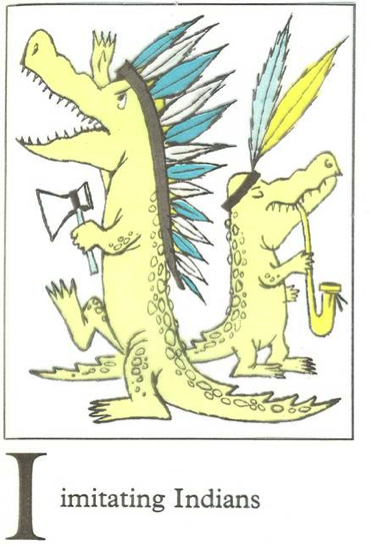

Our TLAM discussions this semester have led me to really think hard about micro-aggressions in day-to-day life. We have spoken about ‘the mascot problem’ and other cultural insensitivities that are prevalent in the world we live in, and this week we got to tackle the subject of children’s literature. I immediately thought of the problematic “I is for Indian” motif that is repeated across children’s books.

To help us to really understand the complexities within this genre, we had the pleasure of a Skype conversation with Debbie Reese, author of the American Indians in Children’s Literature blog. She spoke candidly with us about the scarcity of resources in children’s literature that deal with real Native American issues and the importance of indigenous knowledge in educating Native American children.

First of all, Ms. Reese spoke with us about her own story as a member of the Nambe Pueblo tribe in northern New Mexico. To explain the importance of indigenous knowledge, Ms. Reese used the example of dance, but said that there were many ways that this form of knowledge was utilized in Native American groups. Most importantly, Ms. Reese articulated that there is simply not enough literature that speaks to indigenous knowledge. Furthermore, much of the existing curricula isolates Native American children, often causing them to do poorly in school or even drop out.

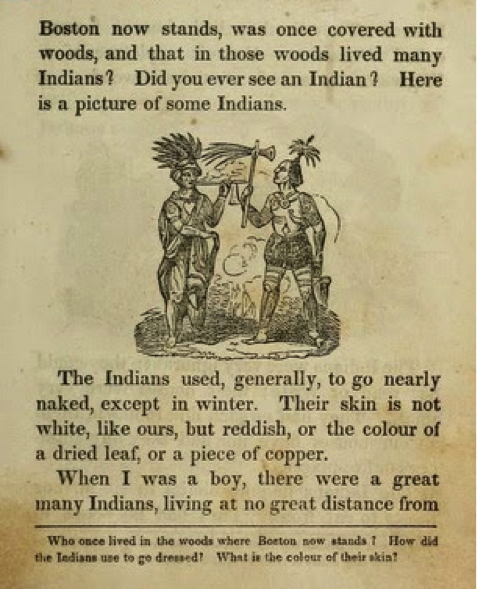

published by Thomas, Cowperthwait & Co. in 1847

She asked us to imagine being a child at a story-time or in a classroom. As Ms. Reese describes on her blog some of the images found in storybooks “depict Native people in grotesque and savage ways; some depict Native people in romantic and noble ways. Some mock Native people in cartoonish ways, while others objectify Native people.” How would we feel seeing caricatures of ourselves being presented in History books or stories? Even worse, how would we feel having someone we trusted as an educator propagating these stereotypes?

published by Little Golden Books in 1951

This became the basis for our conversations moving forward as we explored the many ways Native Americans are wrongly represented in children’s literature in particular. I had not realized just how many harmful, exaggerated images of Native Americans crept into my subconscious through various books and movies that I had seen throughout my life. I began to reflect on some of the books I read as a child with the following questions:

- How many of those had American Indian characters?

- How were they portrayed?

- What was their role in the story?

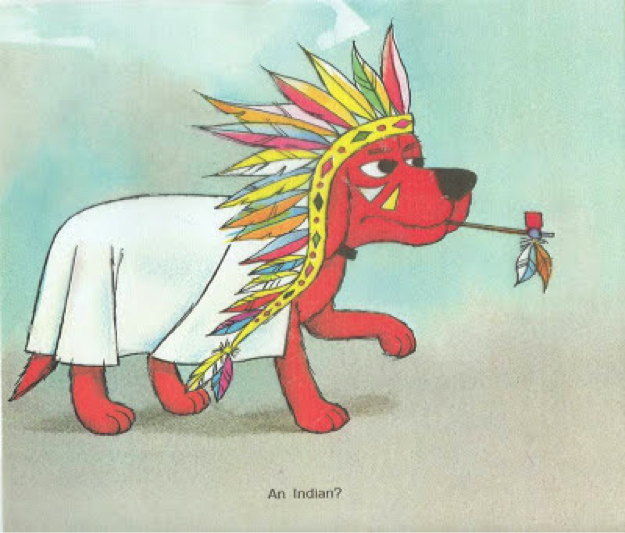

I found that typically, these characters were incredibly simplified or generalized caricatures of Native American people. Our class had a shocking revelation that some award winning books are incredibly insensitive to Native American cultures. Even Clifford had a moment when he was dressed up as an Indian – this typically happy-go-lucky dog was now transformed into a stoic, pipe-smoking dog in a feather headdress.

published by Four Winds Press in 1967.

Ms. Reese concluded her talk by giving us the following set of considerations for choosing culturally sensitive material for both library and personal collections:

- Who is this book about? Is it tribally specific?

- When is the book set? Past or present? (We are currently lacking books with a modern understanding of Native Americans)

- Is there loaded language? (A great example of this is: when there is a conflict is it called a battle when white people win and a massacre when Native Americans win?)

- What about incorrect use of language? (Even in the New York Times crossword puzzle you can find a clue “What is the native word for baby” or “Brave baby?”. The intended answer, “Papoose”, oversimplifies the complexities and variance of Native American languages)

Ms. Reese’s blog has a number of recommended titles that you can use to start to create a collection that is sensitive to the diverse needs of Native American readers, especially children. I look forward to exploring some of those titles in the weeks to come. Hopefully we can begin to make changes in the way Native Americans are represented in literature by simply keeping these questions in mind anytime we come across these characters in books.

-Kathryn Sheriff