Not content to stop at the borders of our country, we spent a week learning about TLAM efforts abroad, which came with mini-lessons on other indigenous groups. For our penultimate discussion, the class was broken up into four pairs, each of which was assigned a different indigenous group or geographic area to research independently: Australia, New Zealand, the Sámi, and Canada.

Australia: Torres Strait Islanders, Aboriginal Australians

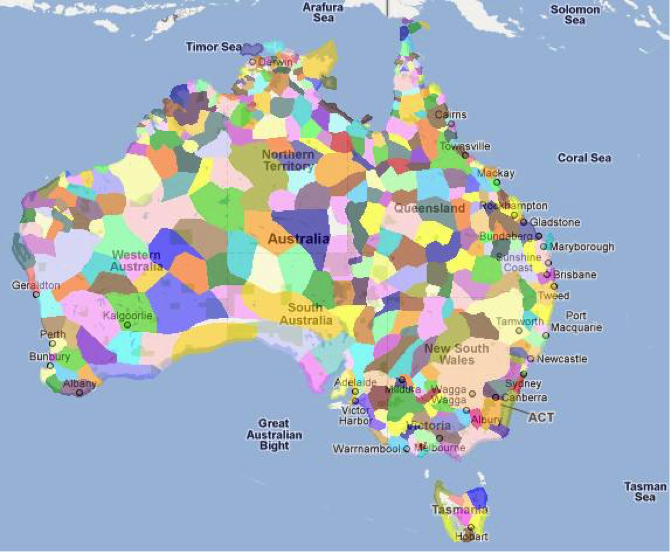

Even considering Australia’s size, there is a shockingly large number of indigenous groups in Australia. Aboriginal Australians are not one group, but hundreds of groups who cover immense geographic ranges and celebrate incredible cultural diversity. There are some remarkable – and tragic – similarities between the treatment of indigenous peoples in Australia and in the US: for instance, Aboriginal Australians mourn the loss of the Stolen Generation, tens or hundreds of thousands of Aboriginal children (it’s unknown exactly how many) forcibly taken from their families in the first 2/3rds of the 20th century and placed into institutions.[1] Sound familiar?

Map of Aboriginal language groups – there are even more Aboriginal tribes than there are language groups! Photo credit: the Queensland Museum Network Blog.[2]

Our classmates told us about the Living Archive project: a digitization project to preserve bilingual educational materials produced in Australia’s Northern Territory by a program that was eventually shut down. These bilingual materials serve as a valuable resource for current language revitalization efforts, and need digital preservation in order to tell their story of Australia’s past and improve the future.

Aotearoa/New Zealand: Māori

The Māori are leading the world in their efforts to integrate indigenous knowledge, issues, and lifeways into libraries, archives, and museums. This includes integrating traditional spiritual beliefs into information organization systems: as our classmates explained, the Māori Subject Headings use a hierarchical model that echoes the Māori’s hierarchical culture and encapsulating worldview, recognizing descent lines for things and activities and assigning subject headings accordingly. This incorporation of indigenous knowledge into information organization systems is apparent throughout New Zealand/Aotearoa’s (Aotearoa is the Māori name for New Zealand) national institutions, which are all bicultural: New Zealanders are expected to know about Māori culture, history, language, and etiquette.

Libraries seem to be particularly good at this biculturalism. The National Library of New Zealand celebrates strong ties with the Māori, who represent a large portion of the population. Māori concepts and words are melded into mission statements and everyday vernacular, and libraries support language revitalization efforts and treaty claims, give input on UNESCO proposals, and put on programs celebrating Māori history and knowledge.

Northern Europe (Finland/Norway/Sweden): Sámi

The Sámi are indigenous to Finland, Norway, and Sweden, and were historically closely connected to and dependent on reindeer – herding them, and using their products to survive. Today, the Sámi live modern lives, although many of them still live in remote and difficult-to-reach areas. Their small numbers and remote locations require special services and strong government support to ensure that they are adequately served, and their cultures don’t disappear.

Students presented on plans created separately in Sweden and Norway to create a more unified set of library qualities and services to better serve Sámi populations, including the creation of national depositories for Sámi language materials, enhancing knowledge and appreciation of Sámi languages, and funding bookmobiles to provide library services to remote groups of Sámi. Additionally, T.G. Svennson argued for the importance of biographical narratives in object descriptions in museums: objects are meaningless, he argues, without information of and from people associated with those objects – creators, family members, histories, etc.[3]

Canada: First Nations peoples

Challenges facing First Nations peoples are similar in many ways to those facing Native American and Alaska Native peoples; however, our classmates found several themes to discuss. On a national level, Brian Deer’s classification schema continues to develop and provide libraries with a culturally competent way to classify materials. Additionally, trauma from boarding schools continues to affect the transmission of knowledge between generations: because children were torn from their homes and deprived of their native languages and lifeways, much knowledge and many stories were lost.

Small libraries play particularly significant roles in serving indigenous communities in Canada: for instance, many such libraries put on community reads for First Nation communities, choosing First Nation and/or Inuit materials and having them endorsed by the tribes; and Ontario celebrates First Nations Public Libraries week every year. Canadian library literature stresses the importance of community partnerships in indigenous communities. However, finding sufficient funding is extremely difficult for small libraries.

As this week made abundantly clear, TLAM issues are not only intensely local, but intensely global – making our TLAM colleagues around the world amazing allies in battling challenges to indigenous communities. There is so much work still to do, but with such a diversity of peoples to contribute solutions, opportunities to learn and grow are everywhere, if we just expand our boundaries.

-Abigail Cahill

[1] Professor Maggie Walter, course: “Indigenous Studies: Australia and New Zealand.” https://www.open2study.com/courses/indigenous-studies

[2] https://blog.qm.qld.gov.au/2012/11/06/message-sticks-rich-ways-of-weaving-aboriginal-cultures-into-the-australian-curriculum/

[3] Svensson, T. G. (2008). Knowledge and artifacts: people and objects. Museum Anthropology, 31(2), 85-104.